Create Your First Project

Start adding your projects to your portfolio. Click on "Manage Projects" to get started

manet / degas

location

metropolitan museum of art, nyc

date

october 21, 2023

this new exhibit at the met directly compares the master works of Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas, chronologically analyzing their artistic relationships that directly influenced and contrasted with each other. although they were born just two years apart (Manet in 1832 and Degas in 1834), and both the eldest sons of Parisian upper-middle-class families, their artistic paths could not have been more different. Manet and Degas had a mutual respect for one another, either through friendship or rivalry, that developed many significant dialogues within nineteenth-century french impressionist art.

descriptions are copied from the met's written plaques for each work.

Although Manet often sat for portraits by fellow artists, this is one of only two known painted self-portraits. He presents himself both as a painter, holding the tools of his trade, and as a Parisian dandy, in his black felt hat and yellow jacket. The rapidly sketched, seemingly unfinished hand echoes the quick action of the artist at work.

In the drawing, Degas rendered Manet’s face in fine detail while his body and the drapery of his overcoat are more freely sketched in long, brisk strokes— an approach he likely adopted from the great French portraitist of the previous generation, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. The more regular hatching of the etching evens out the contrast between the head and body.

This work is a version of Manet’s "Déjeuner sur l’herbe," the startling depiction of a picnic scene with two nearly naked women in the company of fully clothed men that became the artist’s first succès de scandale in 1863. The painting draws on his study of famed Italian Renaissance artworks, yet reframes those references into an entirely new style and context. Rejected by the official French Salon in 1863, it was hung instead at the Salon des Refusés, where it won him immediate notoriety. The broad strokes and seemingly quick application of paint in the version he exhibited belie the fact that the artist worked on the composition for a good year before showing it. This work may have been part of that preparatory process.

Presented at the Salon of 1865, Olympia generated outrage among critics and the public for its frank representation of a contemporary courtesan painted on a grand scale and in a manner some perceived as flat, coarse, or dirty. Manet adapted the composition from Titian’s "Venus of Urbino" (1538) -- a painting he had copied at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence-- and subverted traditional academic approaches to the nude, including conventions of idealized beauty and guises of mythology. Olympia gazes at the viewer with unabashed directness, while her maid brings flowers, perhaps from a client. For his models he cast Victorine Meurent, who had previously posed nude for "Déjeuner sur l’herbe," as Olympia; and Laure, who appears in two other paintings by Manet, as the maid. Laure’s presence alludes to the burgeoning free Black community in Paris at this time.

Olympia occupied a notable place in Degas’s collection. The artist owned an impression of the third state of this print, as well as a larger etching Manet

made after the composition, a drawing on tracing paper, a wood engraving, and a copy painted by Paul Gauguin, which hung prominently in the vestibule of his apartment. Manet produced this etching for a pamphlet written by Émile Zola that was published to coincide with the artist’s 1867 solo exhibition. The constraints of that format resulted in the horizontal cropping and compression of the composition.

Degas exhibited this painting in the Salon of 1866, marking his first presentation at the prestigious venue of a subject drawn from modern life. The steeplechase was a dangerous cross-country race that gained in popularity during the 1860s. In depicting a dramatic, potentially tragic, moment from a contemporary sport, Degas certainly drew inspiration from Manet’s "Episode from a Bullfight," which he had seen at the Salon two years earlier; even the generic formula of the title is similar.

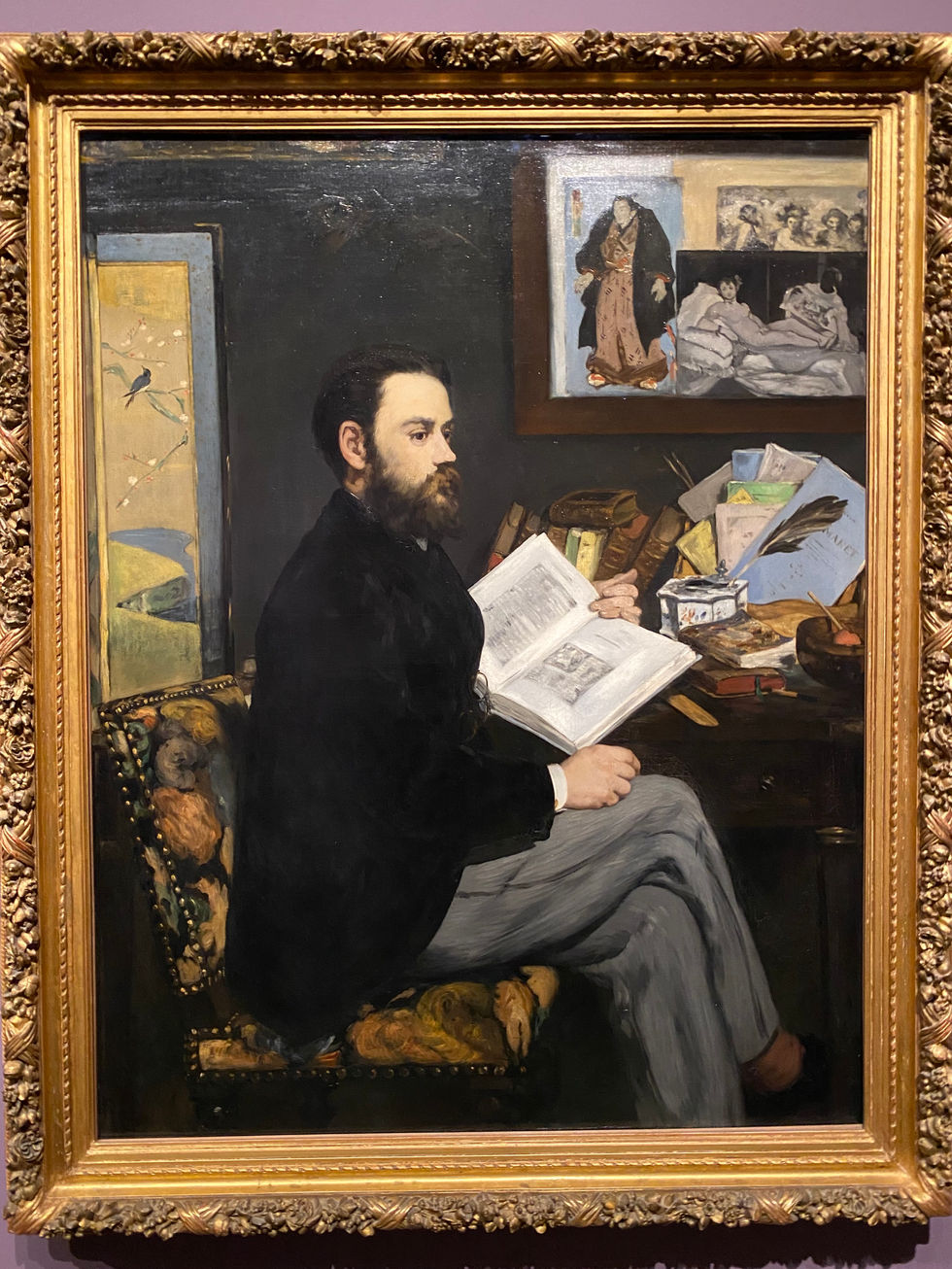

Manet painted this portrait of the writer and critic Émile Zola in recognition of his recent support for the artist in the press. He is surrounded by attributes of his occupation, such as books, a quill pen, inkwell, and his 1867 article praising Manet, which appears as a blue pamphlet propped on his desk. The framed collage of prints on the wall echoes a device that Degas used in his "Collector of Prints" two years prior. Here, Manet included a photograph of his own work, Olympia -- a “masterpiece” worthy of the Louvre, according to Zola -- as well as a Japanese woodcut by Utagawa Kuniaki and a print after Diego Velázquez, both of which point to his artistic influences.

This work originally formed the lower half of a larger composition titled "Episode from a Bullfight," which Manet exhibited at the Salon of 1864. Its subject reflects the current enthusiasm for Spanish culture, though it is not a scene Manet had witnessed firsthand; his first visit to Spain would occur the following year. Critics faulted the spatial relationship and relative scale between the bull and figures in the background and the fallen toreador in the foreground. Heeding this criticism, Manet cut the canvas in two and displayed this portion with a new title at his solo exhibition in 1867.

Among the eleven portraits in oil that Manet made of Morisot, this work is distinctive for the arresting gaze of the sitter, who is framed in a virtuosic composition of blacks. The striking beribboned hat and scarf signal her status as a fashionable Parisian, and the bouquet of violets clutched to her chest, a token of affection, hints at a flirtation. The journalist and critic Théodore Duret originally acquired the painting. Morisot purchased it when it came up for sale in 1894, the year before she died.

Degas painted this portrait of Manet’s younger brother Eugène to mark the occasion of his marriage to Berthe Morisot and offered it to the couple as a wedding gift. It stands out among Degas’s portraits for placing the sitter in a landscape. Both the outdoor setting and his reclined posture recall Manet’s "Déjeuner sur l’herbe" (1863), for which Eugène had similarly posed, holding a walking stick. Degas exhibited this work at the second Impressionist exhibition, in 1876, along with the oil sketch of Eugène’s sister-in-law, Yves Gobillard, also on view in this gallery.

Madame Morisot described Degas’s process of making this portrait of her daughter Yves: “He took a big sheet of paper and set to work on the head in pastel. He seemed to be doing a very pretty thing and drew marvelously. . . . He seemed satisfied with what he had done and was annoyed at having to tear himself away from it. He really works with ease, for all of this took place amid the visits and the farewells that never ceased during these two days.” Degas showed this pastel in the Salon of 1870. It was the last time he exhibited at that venue.

Étienne Moreau-Nélaton, a champion of Manet’s art and a collector who owned, among other works, his "Déjeuner sur l’herbe," pointed out that the artist owed his interest in the subject of the racetrack to Degas. Degas’s drawing of Manet at the races, shown in this gallery, confirms that the two artists were there together. Manet may have corroborated this evidence; the spectator in the top hat at the bottom edge of this painting is possibly Degas.

Degas often painted on a sheet of paper that was then mounted on canvas. Here his medium was essence -- oil paint thinned with solvents -- which he worked like watercolor on paper. To that end, he left the sheet blank in many places to make highlights and applied the paint like a stain to create the dark shadows cast by the sharp sunlight. Unlike Manet’s contemporary "Races at Longchamp," which conveys the adrenaline-fueled excitement of a thundering finish, Degas’s composition frames the horses and their jockeys during an off moment, apart from the action. Whether real or imaginary, the racetrack served as the artist’s stage for a strikingly modern scene, setting a bourgeois leisure activity against an industrial landscape of billowing smokestacks.

This painting captures the excitement of the popular Longchamp racetrack in the Bois de Boulogne, on the outskirts of Paris, which opened in 1857. Whereas Degas’s racetrack paintings often focused on the moments at the start of a race, Manet here recorded the last stretch, as the horses rush past the finish line, indicated by the raised flag and the pole with a circular top. Manet shunned traditional representations of the sport, which showed races from the side, and instead composed the scene so that the throng of horses and jockeys thunders straight toward the viewer.

During his sojourn in New Orleans, Degas painted the lively office of his family’s cotton business. The artist’s maternal uncle, pictured in the foreground, assesses the quality of the valuable commodity, while his brother René reads the local Daily Times-Picyune and his other brother Achille leans casually against a counter at left, looking on as employees busy themselves with activity. Degas had hoped to sell the painting to a cotton spinner in Manchester. Ultimately acquired by the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Pau in 1878, this work was the artist’s first to enter a public collection.

Manet summered at Gennevilliers in 1874, often spending time with Monet and Renoir across the Seine at Argenteuil, where "Boating" was painted. In this scene of outdoor leisure, he not only adopted the lighter touch and palette of his younger Impressionist colleagues but also borrowed the broad planes of color, strong diagonals, high vantage point, and close cropping typical of Japanese prints. Rodolphe Leenhoff, the artist’s brother-in-law, is thought to have posed for the sailor, but the identity of the woman is uncertain. Manet exhibited this painting at the Salon of 1879.

In July and August of 1874, Manet vacationed at his family’s house in Gennevilliers, just across the Seine from Argenteuil, where Claude Monet and his family lived. The two painters saw each other often that summer, and on a number of occasions they were joined by Auguste Renoir, who painted the Monet family alongside Manet en plein air. Monet and Renoir joined Degas in organizing the first Impressionist exhibition that year. Manet did not participate; however, he supported the group and was certainly influenced by them. Despite taking on similar subjects, such as this outdoor family portrait, and incorporating looser brushstrokes in response to their work, his scenes retain the solidity in their paint handling that was a hallmark of his oeuvre.

In this unfinished portrait, Manet depicts the Irish writer George Moore at the popular Café de la Nouvelle-Athènes, a gathering place for artists and writers, where the two probably met. Moore’s writings are filled with observations about Manet and Degas and their relationship. In "Modern Painting" (1893), he recounts an evening at the Nouvelle- Athènes, “passed in agreeable aestheticism,” and describes the two painters’ contrasting characters: “Manet loud, declaratory, and eager for medals and decorations; Degas sharp, deep, more profound, scornfully sarcastic.”

Following Degas’s "In a Café (The Absinthe Drinker)," Manet evoked the same setting of the Nouvelle-Athènes and selected the same model, the actress Ellen Andrée, for his own café scene. Although centered on a woman alone with her drink, which in popular imagery of the time often implied moral indecency, her identity is ambiguous. Resting her head in hand, as she ignores her brandy-soaked plum and unlit cigarette, she gazes wistfully into the distance, conveying a sense of urban isolation similar to that evoked in Degas’s painting.

In this work, Degas portrayed an archetypal café-concert star by combining the trademark gesture of Thérésa, the stage name of Emma Valadon -- one of his favorite performers at the Alcazar -- with the features of another model. In December 1883, urging a friend to go right away to see Thérésa perform, he exclaimed, “She opens her big mouth and there emerges . . . the most vibrantly tender voice imaginable.” In the mid-1880s the artist experimented with saturated hues and color contrasts, evident here in the vivid yellow, turquoise, and orange of the singer’s dress.

Bathers continued to preoccupy Degas as a subject in the late 1880s and into the 1890s. Through the creation of variants on this theme, he experimented with the pastel medium. In this work, he applied the strokes in many successive layers, juxtaposing shades of chartreuse, green, and blue with pink and orange, perhaps playing with ideas of optical color mixing investigated by his younger contemporaries such as Georges Seurat.

When Manet returned to the theme of the female bather in the late 1870s after more than a decade, he placed his subjects in distinctly private settings. Here, a woman wearing only stockings prepares a bath, bending over a shallow tub against the backdrop of a curtained vanity. His application of the pastel medium, a newfound interest for the artist, is boldly spare. In subject and technique, this work recalls similar pastels by Degas depicting women bathing and at their toilette, which Manet may have seen at the third Impressionist exhibition, in 1877.

Napoleon III of France installed Maximilian as Emperor of Mexico in 1864, only to recall his support in the face of resistance from Mexican republican forces and threats from the United States. The 1867 execution of Maximilian with two of his generals inspired Manet to undertake the most ambitious of his artistic projects based on current events. He worked for several months on a large composition intended for the 1868 Salon, producing four paintings and a lithograph. Too politically controversial to be shown to a Parisian audience, none of the paintings were exhibited in France during his lifetime. Left in his studio, they were seen only by a few of the artist’s close associates, including perhaps Degas. This painting was cut into pieces -- it is unclear whether Manet was responsible -- which were sold off to dealers and collectors after his death. Degas painstakingly acquired the fragments and mounted them on an enormous canvas that hung at the center of a museum-like gallery on the first floor of his apartment. This work was in Degas's collection.